Nigeria

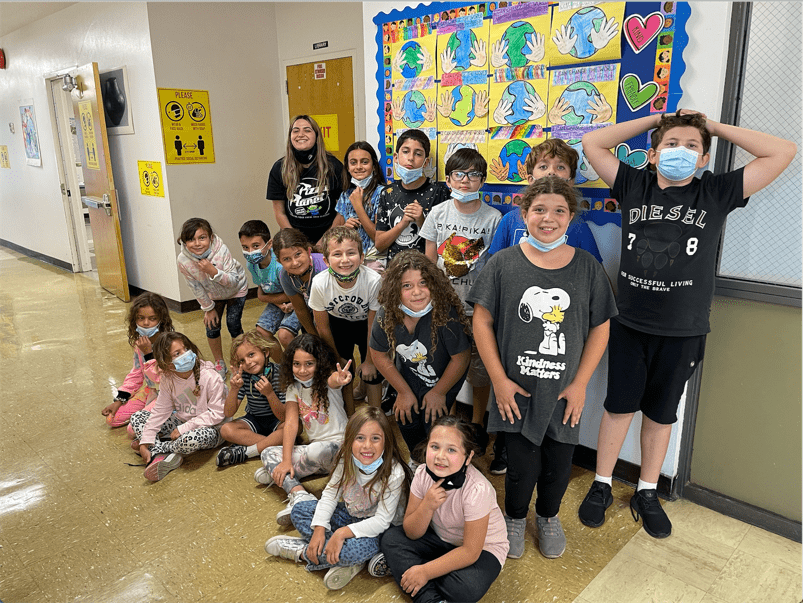

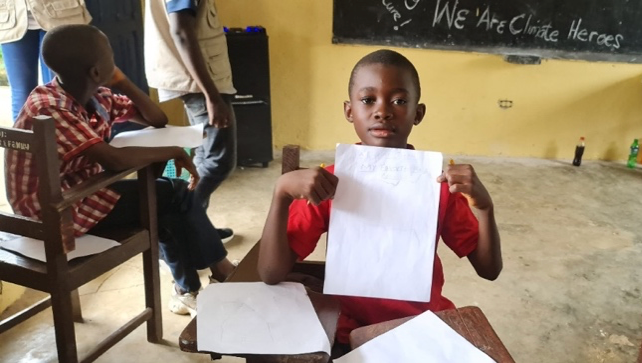

Below, some of the schools inspired by their wisdom exchanges: 1. Students from New Day School who joined in the movement locally; 2. Nigerian learners farther away, in Oghun State, conducting health checks in a church; 3. The team from St. Thomas School in Zambia, writing letters of advocacy for the wisdom exchange; 4. Zambians conducting malaria prevention; and 5. Cameroonian children spreading awareness of breast cancer.

Winter 2021-Spring 2022: Nothing heals quite like empathy, the universal remedy.

One student-led “wisdom exchange” began in the secondary grades of the Harvard International school, in the Delta region of Nigeria, where students ultimately shared health education concepts with 20,000 households in 2021. They followed a systematic process to do so. Their learning unit theme, Awareness, included discussions about the factors that promote equity and that keep societies healthy. Students met with the region’s medical director, who identified the area’s most relevant health risks and treatment disparities, focusing especially on Lassa fever among vulnerable populations.

Because of the disease’s relative obscurity, the students, in their first academic unit, set a goal of heightening awareness of Lassa fever among nearby residents. They began walking door to door to help households understand their own health risks and guide them in safely clearing up rodent infestations. After their early successes, the school’s Health Disparities Team traveled to another town and then to another. Next, they presented information at multiple schools, to deputize and educate peers as public health advocates. Ultimately, they reached households in five towns with their message, tracking statistics as they measured the impact based on the average number of individuals in a household.

Officials urged the school to expand its efforts, confident in the students’ emerging expertise and strong commitment to the common good. The school no longer needed to solicit health agencies for information, as government departments began to reach out to them as a resource, tasking them with public education about the next set of health priorities--malaria, diabetes, and high blood pressure—according to project leader Harry Kennedy.

Another development convinced officials to reach out to the school, Kennedy reported. A conspiracy theory had led some citizens to discredit government health advisories, believing the intention was to increase the mortality rate and reduce the size of the population. With government-sponsored public awareness programs decreasing in their effectiveness, officials felt compelled to cultivate new trust builders.

The confidence placed in them helped cement students’ sense of purpose as they reached across cultural and national boundaries. Seeing the results, the Education Ministry requested teacher training programs for educators at other schools. Kennedy remarked that the movement had begun to “revive our national system. This program is making a great difference in the lives of the children.”

Meanwhile, wisdom exchange partners in two Zambian community schools, St. Thomas and Lushomo, began to mitigate the spread of typhoid. (A community school is defined as a typically free school for low-income learners, operated by parents, as opposed to tuition-based public or private schools.) In many of the schools, teachers strive to teach the national curriculum with little or no pay, while implementing an additional mission of fostering humanitarian goals. The Zambian learners compared their own disease prevention process with that of the Nigerian students at Harvard International. They visited health professionals to learn the causes and effects of typhoid. They created educational materials to carry out neighborhood awareness campaigns and environmental cleanups. They wrote letters back and forth with the Nigerian partners about best practices to build public trust. They conducted conflict resolution exercises to address tribal resistance to adding chlorine to drinking water. Through their correspondence with the Nigerian students, they also learned about the causes of the vector-borne disease Lassa fever, previously undocumented in Zambia.

The Zambian students later contacted their environmental health technician about their findings with the Nigerian students concerning Lassa fever and initiated a pledge to add it as a research topic, to determine the possible existence of Lassa fever outbreaks in their country. Zambian Full-Circle Learning trainer Eric Muleya expressed amazement at this unanticipated wisdom exchange outcome. Originally the educators had anticipated an exploration of community-trust building and the process of reducing health disparities. When a community school directed its nation to explore a previously untreated disease, he remarked, “Essentially, these young students are realizing their capacity to influence global health!”

The schools within each setting grew into their roles as ideal trust builders, enhancing the work of health agencies, clinics, and civil society organizations even beyond their own borders.

The Nigerian team continues their work, expanding into new regions of the country. The health disparities team recently made a six-day trip to Oghara, a town in Delta State, to educate the people about hypertension and diabetes and checking blood pressure and blood sugar.

The team discovered a group of men drinking under a tree and began to talk with them. They discovered these men were ignorant of the link between alcohol consumption and high blood pressure but were grateful to learn about this important piece of their own health. They all decided to take the team’s advice in future, limiting their alcohol consumption and eating the healthy foods the team recommended.

Another elderly man in the Oghara community suffered from stiffness in his hands and legs. The team had a massaging machine they used on the man during their stay in Oghara, relieving his pain.

When the team went to teach in the town’s park, some locals were suspicious because, in their experience, healthcare workers had rarely visited the park before. The team assuaged their fears, sharing their informational materials and checking the blood pressure and blood sugar levels of those gathered there. By the end of the team’s time in the park, one man prayed for the team and their work. He had been trying to get his blood pressure and blood sugar checked for a long time but had been too busy to get to the hospital for an appointment.

In total, the team reached more than 15,000 people during their six days in Oghara, giving the town a strong public health foundation for the future. They exchanged contact information with local people to maintain these new connections over the long term.

April 2022: Global Harvests that Harmonize Hearts

“Let them stare. Let them see. We will show the world harmony,” sang school children from the Osun State of Nigeria to immigrant children in Los Angeles County, in response to a recent Full-Circle Learning wisdom exchange.

Earlier in the school year, Tarzana Elementary School’s Habits-of-Heart students set out to plant seeds of kindness. Their teacher helped them integrate academic and arts projects and send a wisdom exchange package, including hand-made gifts of tie-dyed shirts, to classmates across the ocean. Each child penned a list of inquiries to their new brothers and sisters, sharing their own upcoming plans to grow real seeds of kindness in a community garden.

They sent their package at a time when shipping delays plagued the US Postal Service. (For a time, we wondered whether the large box would ever get as far as Lagos, let alone to the village.) After many calls to the customs office, the Nigerian wisdom exchange liaison finally reported its arrival. Her delighted students wrote replies about their own farming projects and their process of making dye from vegetables. Their Unity Class (grades 2-3) had grown local plants as gifts for teachers. Their Patience Class (Preschoolers) had grown maize and cassava to feed the community. Their first-grade Cooperation Class had honored local orphanage founders for kindness.

Cherishing the letters and wearing the shirts, the Nigerian children sang the Harmony song and videotaped it for their faraway family in the town of Tarzana. Meanwhile, Tarzana’s principal shared the story with joyous parents, many of them immigrants themselves. The Full-Circle Learners enjoyed knowing they could sow seeds of kindness abroad and watch them sprout.

When learners, teachers and colleges all work for the common good, society transforms. We have witnessed this phenomenon around the world—now more than ever.

The Director of the Doxavil International School Oghara, in Nigeria, said that Full-Circle Learning programs made his school the best in the region. When promoted to become provost of the Mosugar College of Education, he quickly acted to train graduating student teachers from two colleges and to launch the FCL course, Why We Learn, into Nigerian teacher education. He told them about the sweeping reforms he had seen as a principal among learners engaged in Full-Circle Learning.

Maverick Nigerian Full-Circle Learning Facilitator Harry Kennedy has helped such K-12 schools break new ground in the Delta State. His own students helped more than 20,000 Nigerians prevent malaria and infectious disease and monitor chronic health conditions such as hypertension and diabetes. Now Harry has set his sights on eradicating another disease—teenage addiction. During the school break, he sponsored a long-term camp to offer a sense of purpose for youth leaning toward dangerous lifestyles, guiding these teens to embrace their own power to become tomorrow’s young leaders.

The Fabric of the Human Family

Why Are These Children Dyeing to Give?

Creativity Builds Community

Full-Circle Learning students celebrate the intersection of life skills, scholarship, the arts, and community giving. Service projects sometimes honor mentors or elders who demonstrate these community transformation skills.

For example, Nigerian students at the Estate Community Primary School, in Osun State, spent three weeks learning the art of batik, dyeing waxed cloth in rich patterns.

During this training, they embraced the habit-of-heart of creativity—not only in their artwork, but by seeking creative paths to enrich their community. The children sensed that happiness in the human family depends on the fabric created in their own classroom family.

In a first step to giving back, the students’ honored their batik instructor, Abel Alfred, a local artisan who graduated from the school himself some years ago. They chose some of their best work to offer to Mr. Alfred as a gift.

Help Full-Circle Learning’s students transform their communities with creativity.

Please click below to donate today.

Students Halt a Killer in the Air

Young leaders across Africa are fighting malaria—and winning.

Exchanging Wisdom to End Disease

Across Africa each year, 215 million people suffer from malaria, according to the World Health Organization. In some regions, the death toll surpasses that of Covid-19. When malaria strikes a community, 67% of the dead are children—but Africa’s children also lead the campaign to make malaria a problem of the past.

Full-Circle Learning students realized that tackling any public health crisis begins with the habit-of-heart of awareness. Schools in Liberia, Nigeria, and Zambia currently work together to spread the awareness that can protect communities from malaria.

In Nigeria, Harvard International students traveled across the region to galvanize peers as health advocates in their effort to save lives. A team of student researchers learned from their visit to a local hospital and taught their new knowledge to their classmates for a half an hour daily. Via cell phone, they met with learning partners abroad. Inspired by this international exchange of wisdom, they next traveled to another town, Umutu, where they visited six schools and trained 2,700 children and 170 parents to act as health advocates. In the photo above, the students are on the road to make this change.

Meanwhile, the rainy season brought flooding to Liberia. Standing water bred new mosquitoes to carry the malaria parasite. At Ma Vonyee G. Dahn Memorial School, students toured a malaria research lab and a public health department to get the facts. They shared specially treated mosquito nets and information about treatment with families in 14 homes. Elderly and high-risk community members who lived near the school happily received the gifts. Other community members welcomed a public presentation (see photo below) which detailed the steps for mosquito eradication.

Zambia’s Gifteria School also undertook a malaria prevention project. Students, parents, and teachers worked together to clean up the local environment and drain standing pools where mosquitoes could breed. Two local orphanages were especially vulnerable, due to their location near a stream. The Gifteria students visited these orphanages and the surrounding community, mosquito-proofing the landscape and giving treated nets to those in greatest need.

By enhancing their projects through “wisdom exchanges,” each group of global learners accomplished more than they could have on their own. At present, the students continue their public health advocacy to improve the wellbeing of their human family.

Help FCL’s students slap out malaria.

Please click below to donate today.

Full-Circle Learning has served the country of Nigeria since 2017. RegionalFacilitator Harry Kennedy refreshed the training of 30 schools in the Delta region in 2020, guiding them toward various initiatives.

He brought his own community transformation experience to bear in helping students uplift their communities and achieve sustainable development goals. A malaria prevention project helped students ensure equity by raising funds for nets, distributing them among the most vulnerable, and resolving conflicts regarding eligibility for the few nets.

In one project, students from HarvardInternational School offered valuable quotes about the purpose of learning when interviewed about their response to distance learning provided by FCL during the pandemic. (See the distance learning video on this site.)

The school has offered integrated learning strategies to help students engage in various transformational projects such as:

- Malaria prevention​ (advocating with the government to acquire mosquito nets for the vulnerable and managing conflicts incurred in the distribution process)

- Covid-19 prevention ​(gathering and distributing PPE and thermometers for many schools in the region)

- Flood control ​(encouraging the adaptation of a new flood plain and assisting in preparedness measures)

- Uniting the region’s warring tribes ​(through a dance festival to celebrate the talents of all)

- Access to clean water (as the Nikki Foundation helped learners advocate for borehole drilling)

In 2020, Funmilayo Aberejesu also brought her Full-Circle Learning experience gained at Gambian schools back to her homeland in the Osogho Osun state of Nigeria, where she worked with students from the Salvation Army school.

Below, teachers gathered for one of multiple regional trainings in the Delta region.