United States

Mining for Gems at Climate Change Agents Camp 2025

What practices and principles help bridge the path from advocacy to action? A cadre of Climate Change Agents, ages 16 – 21, gathered in the Sierra foothills this July to explore the question. Merit-based scholarships were awarded to the participants, listed alphabetically: Taj Daunch-Greenberg, Aleesha Gilbert, Logan House, Amelia Regan, and Jessica Rivenes. Set in the hills above an abandoned hydraulic mine site, their lodge presented an ideal backdrop for researching the centuries-long impacts of mining not only on habitats and on health but potentially on the acceleration of climate change itself.

Tracing Impact

The youth first studied the principles of "moral ambition" outlined in Rutger Bregman's latest book, and each defined their own potential pathways for improving life among all sentient beings.

The data collection then began, as they mapped out tree dimensions and quantities to compare the features of the abandoned mine site, a nearby wildland-urban interface, and a managed forest. On each 200-foot plot, the young researchers counted the number of trees and identified the number and location of older-growth trees (60 inches or greater in diameter). They observed that the soil in the heart of hydraulic mining no longer supported indigenous trees but mostly low-growing manzanita shrubs, which had spread like ground cover. As a result, the reduction in shade had actually increased the air temperature of this study plot.

At the second site, a network of conifers thrived, fed by a stream and connected by their underground root system in the wildland-urban interface. The developers had carefully protected the largest of the old-growth trees intact. Still, wildlife habitats were interrupted by the prevalence of development and human interventions.

The third location, a managed forest, offered the greatest biodiversity. It featured thriving deciduous trees—maple, alder, and dogwood—in a riparian ravine moistened by Deer Creek. The portion of the trail once crowded with second-growth plantation trees had been thinned to discourage wildfire, while leaving old-growth trees intact to serve as the mother trees of the ecosystem.

In their follow-up discussions, the youth began to see science as a series of puzzles and questions, for which potentially more than one right answer exists. This idea later became relevant when Audubon Society representatives presented information on the various impacts of climate change and mining on bird habitats. As canaries in the coalmine, changing bird populations reflect impacts such as habitat destruction, shifts in migration and breeding grounds, response to pollution, and more. Discussions reverted to tips for helping birds in an ever-changing climate.

As if to emphasize the point, this year's nighttime owling experience proved challenging. The new location lacked the abundant food sources encountered in previous years down valley. Finally, the group moved to a hilltop elevation and eventually heard a distant screech owl, but the owl did not approach the camp, breaking a years-long pattern of sightings in healthy mixed conifer forests.

Addressing the Needs of the Vulnerable

While wildlife attracts advocacy work, so do vulnerable human populations. Eager not only for research but for service, the students visited the energy-efficient home designed by Eric Jorgensen to expand their understanding of ways to reduce carbon emission. Next, they conducted an energy audit at Utah's Place, one of the homeless facilities operated by Hospitality House. The managers, along with Eric, led them through various parts of the facility, explaining which energy improvements had been conducted and what needs remained. The group identified four recommendations that would reduce energy costs and emissions and increase the comfort level of the guests. The Climate Change Agents then sent the Hospitality House board of directors a letter encouraging them to support these recommendations. They also advocated that the insights of the staff result in allocation of additional resources toward energy efficiency.

Can We Have It Both Ways?

Nuanced impacts and actions had come into play by now. A primary focus of the camp, scientific paradox, led the youth to also practice the unifying conflict resolution skills that unify the goals of diverse environmental activists. For example, innovative manufacturing industries in the global south mine the rare earth metals needed to meet the consumer demand for renewable energy. However, in so doing, the factories have created counterintuitive, negative impacts on climate change mitigation through the mining of lithium, cobalt, and other rare earth minerals. Ironically, the production of renewables threatens to generate toxic tailings, human rights challenges in the developing world, and the release of dangerous pollutants into water, air, and soil.

Considering the centuries-long impact of mining, the Climate Change Agents practiced a conflict resolution exercise between anti-mining activists and pro-renewable activists living in a hypothetical city considering approval of a new EV car factory. Each opposing group offered solutions beneficial to all, such as support for further research and development into improved mining practices as well as the production of renewable resources that don't rely on mining.

Nature Itself as a Solution Giver

These background projects prepared the youth for their final expedition to a local abandoned hard-rock mine site. They studied Dr. Jeff Lauder's research on phytoremediation—use of photosynthesis, as opposed to heavy, gas-powered equipment, to remediate the unhealthy toxins left by mining. In this research study, purple needlegrass, red fescue, and sunflowers proved effective in cadmium uptake and also served as assets to the carbon sink. Dr. Lauder offered historical perspective and ecological insights, and the Climate Change Agents returned the favor by removing invasive species at the mine site, to make more room for the carbon-and-metal-storage plant heroes. The project highlighted the value of innovations that apply natural processes to amend the impact of human interventions.

The youth also engaged in the act of "mining for beauty" in their surroundings. They turned observations of selected natural wonders into art gifts. As a final act of service, each one presented an aspect of their collective research at a gathering, to introduce adults to new insights and pathways of advocacy and action.

During the camp, the team engaged in late-nights collaboration games and introspection on their potential actions in years to come. They demonstrated their capacity to make a difference not just by protesting against but, rather, advocating for the changes that will generate the greatest good. As perhaps their strongest new asset, they deepened their bond with peers who have accepted a role as change agents of the present and future.

Acknowledgements go to the organizations, donors, and volunteers who supported the Climate Change Agents camp. Full-Circle Learning offered curriculum support and supplemental funding. Nevada County Climate Action Now, Sierra Streams, Hospitality House, and Sierra Foothills Audubon Society provided mentors. The latter (SFAS) also provided major donations and fiscal agent support. It took a village to raise the awareness of these young advocates and turn knowledge into action.

Climate Change Agents 2025 Photo Essay

Habits of Heroes Newsletter - Summer 2025

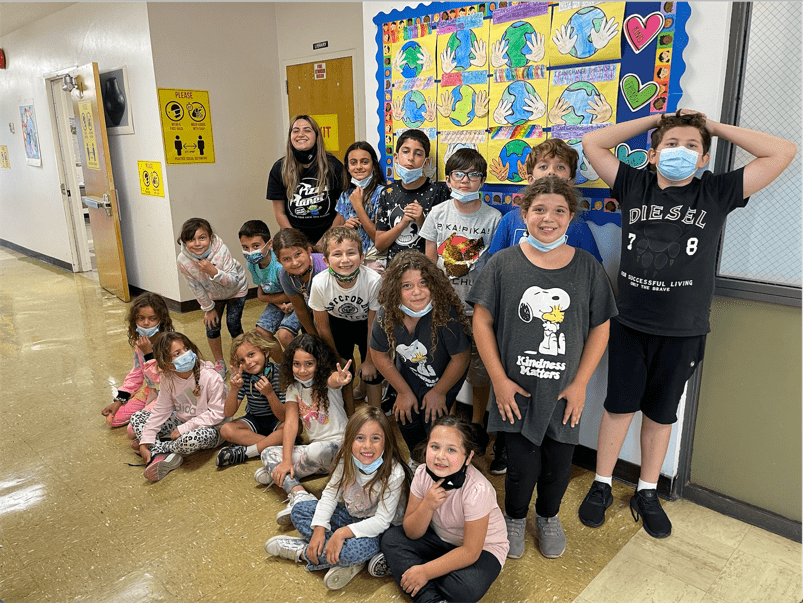

Young heroes in Upland, California expanded their vision, rolled up their sleeves, and opened their hearts this summer, through a special program to support the local Compassionate Communities movement.

Upper elementary and incoming middle school students attended academically focused bridge classes in the morning. In the afternoon, a pilot group enrolled in the half-day Habits of Heroes program at Cabrillo Elementary School. The program resulted from a collaboration between People for Peace and Prosperity, Full-Circle Learning, and the Upland Unified School District's Special Services Department, led by Mario Jacquez.

Over the summer, participants completed four learning units: Vision Seeking, Selflessness, Advocacy, and Dedication. Within each unit, they learned academic concepts and life skills related to the theme. They also honored community role models and participated in relevant service-learning field trips as they strived to master each successive habit-of-heart.

Vision Seeking

On a visit to Brookdale Assisted Living, each child interviewed an elder and honored them for their contributions to society, with handmade gifts and artwork.

The class also exchanged wisdom with a school in Nigeria, to learn from peers about how to develop a vision such as reducing health disparities in a community.

Selflessness

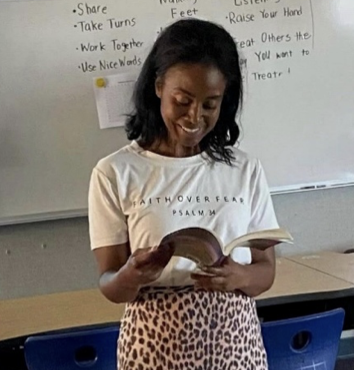

California Botanic Garden docents emphasized ways to speak out for voiceless species. Here, the Heroes gathered around lead teacher Antoinette Wright to explore the garden. Afterward, the class honored docents with a paper flower bouquet.

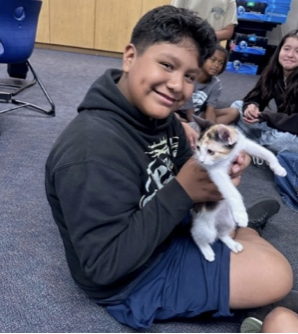

While practicing the habit of selflessness, students also learned about career choices that prioritize the needs of others, They welcomed classroom presentations by veterinarian Dr. Nicole Weinstein (and her kitten assistant) and by a Hospice Chaplain, Reverend Kathleen Reeves.

Advocacy

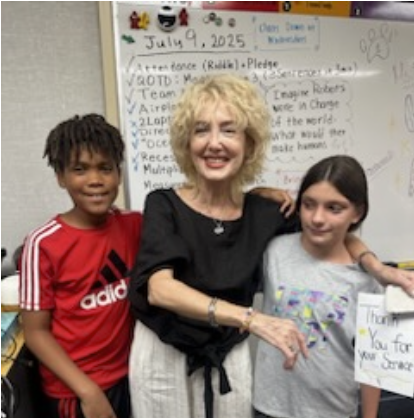

Rancho Cucamonga Superior Court served as the backdrop for understanding how judges, juries, and attorneys strive to create justice and advocate for the rights of both plaintiffs and victims. Students sang to Judge Uhler and toured the facility, offering gifts to thank the staff for their service, after an in-class presentation about dispute resolution by attorney Soheila Azusa (pictured).

Dedication

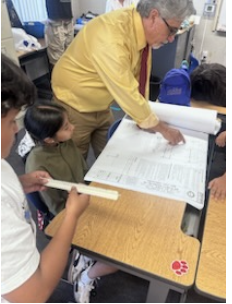

The habit-of-heart dedication, an essential tool for architects, inspired a study of Andrew Carnegie. In the early twentieth century, Carnegie ensured that almost every major city, including Upland, would acquire a distinctive, free public library. Engineer Mehrdad Nosrat taught the Heroes how to create a blueprint for such a facility.

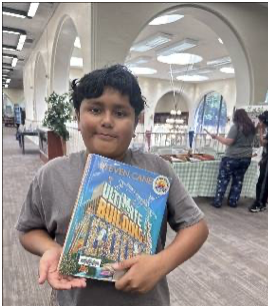

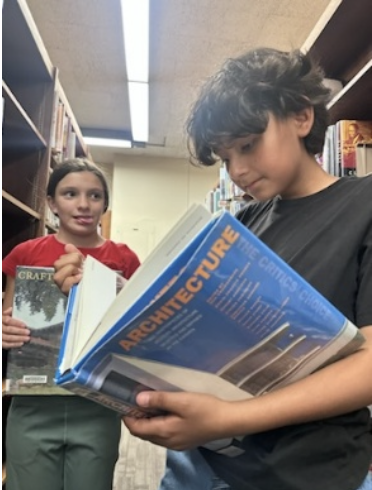

On a trip to the public library, the learners researched designs to inspire their own architectural models.

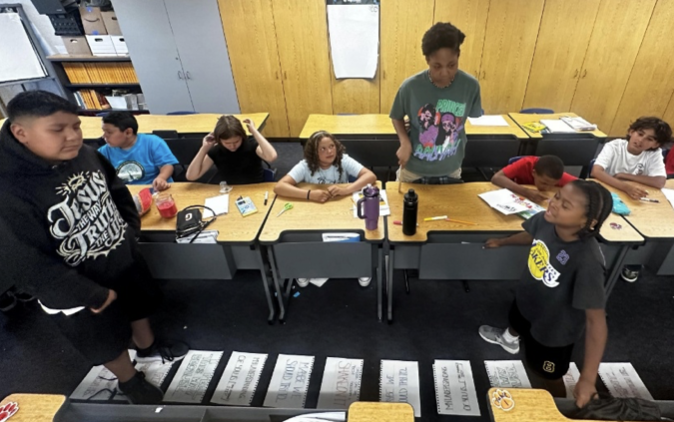

In-Class Highlights

Academic projects infusing art, music, role plays, discussions, and guided imagery (mindfulness) activities prepared students for their community work.

Antoinette Wright led guided imagery exercises based on the book, The Sky Belongs to Everyone. The Heroes took journeys of the mind to reinforce their heroic identities.

Intern Savannah Lindsey mediated each march across the conflict bridge.

Examples of role plays included a sibling dispute about a borrowed item not returned, as well as a conflict between a bus driver and a rider lacking ample bus fare.

The Heroes also acted out their unit themes by playing habit-of-heart basketball.

Intern Sara Dawidian taught a lesson entitled, Art Can Change the World.

The Heroes embraced the concept as they made "Hero" bracelets for community role models, hats to honor elders, and architectural concepts to inspire buildings that benefit society.

JustServe volunteers (right) laid the groundwork for the plan to give paper flowers to docents.

Celebrating Compassion

At the final mastery ceremony, each student received a teacher's certificate for the habit they best mastered.

In turn, the children each presented a Hero certificate to parents or to a caregiver for the habit they most appreciated in that family member.

Those present filled out anonymous surveys, with 100% reporting that their children had improved beyond their expectations in at least 15 of 19 skill sets, including a heightened motivation to learn. The evening ended with pizza, provided by People for Peace and Prosperity, and congratulations for the evolving young heroes.

April 2022: Global Harvests that Harmonize Hearts

“Let them stare. Let them see. We will show the world harmony,” sang school children from the Osun State of Nigeria to immigrant children in Los Angeles County, in response to a recent Full-Circle Learning wisdom exchange.

Earlier in the school year, Tarzana Elementary School’s Habits-of-Heart students set out to plant seeds of kindness. Their teacher helped them integrate academic and arts projects and send a wisdom exchange package, including hand-made gifts of tie-dyed shirts, to classmates across the ocean. Each child penned a list of inquiries to their new brothers and sisters, sharing their own upcoming plans to grow real seeds of kindness in a community garden.

They sent their package at a time when shipping delays plagued the US Postal Service. (For a time, we wondered whether the large box would ever get as far as Lagos, let alone to the village.) After many calls to the customs office, the Nigerian wisdom exchange liaison finally reported its arrival. Her delighted students wrote replies about their own farming projects and their process of making dye from vegetables. Their Unity Class (grades 2-3) had grown local plants as gifts for teachers. Their Patience Class (Preschoolers) had grown maize and cassava to feed the community. Their first-grade Cooperation Class had honored local orphanage founders for kindness.

Cherishing the letters and wearing the shirts, the Nigerian children sang the Harmony song and videotaped it for their faraway family in the town of Tarzana. Meanwhile, Tarzana’s principal shared the story with joyous parents, many of them immigrants themselves. The Full-Circle Learners enjoyed knowing they could sow seeds of kindness abroad and watch them sprout.

Full-Circle Learning has provided teacher training or direct student-service programs at each of these 43 learning institutions in the United States between 1992 and 2020 (photo essay attached):

Arizona

- Professional Development, Nurtured Heart School, Tucson

California

(40 Programs)

Southern California

- Alumni Clubs

- Chapman University Course Materials (Social Justice Education)

- Children’s Enrichment Summer School and After-School programs

- Huntington Hotel FCL School

- Encino Elementary After-School Programs; Encino ProfessionalDevelopment Training

- Full-Circle Learning Alumni Club

- Cleveland Elementary School, Pasadena

- Full-Circle Learning Academy (inner-city charter school)

- King Elementary: FCL-Integrated Science Program

- Oak Park High Full-Circle Learning Club

- Phenomenex: Full-Circle Learning and Leadership and LifeSkills workshops

- Piru Full-Circle Learning Preschool

- Rancho Sespe/Piru Summer school and year-round enrichment program

- SANAD Cultural Preservation School

- Santa Ana School District professional development

- Spurgeon School FCL Program

- Tarzana Elementary: School wide Professional Development and Habits-of-Heart Club

- Topanga Elementary project

- Topanga Global Professional Development Workshops

Northern California

- Climate Change Agents Camp, Nevada County

- Community Education Initiative (CEI) Summer School – El Cerritos

- Diabetes Awareness Camp (co-hosted)

Professional Development Workshops in:

- Plumas County: Teacher Training, Quincy - multiple schools, hosted by local Plumas Audubon Society

- Oakland – Kaiser Corp. Building – Leadership and Life Skills

- San Leandro – Public Library – Full-Circle Learning

- San Francisco – California Community Foundation Building

- San Rafael – Global Wisdom Exchange Training

- Nevada County School District Office – Full-Circle Learning

- Grass Valley (Education as Transformation statewide training)

- Professional Development: Wisdom Exchange: Nevada City

- Professional Development: Service-Learning, Nevada City

- Zeum Museum: Joint Project for Global Schools

Florida

- Gainesville: Regional training workshop

- Hidden Oak reading program

- Prairie View in-school program school

- Jackson: Venus School professional development

- Rawlings Elementary professional development/in-school program

New Mexico

- Albuquerque Professional Development

- Anthony New Mexico/Anthony Texas Professional Development

- Professional Development, Ganado

New Jersey

- Newark School District Professional Development

New York

- New York City School District Professional Development

- Paul Robeson Middle School

Rhode Island

- Children’s Theatre Company